Walter Selywn Crosley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Walter Selwyn Crosley (30 October 1871 – 6 January 1939) was an

During the

During the

In December 1899, he transferred to the and remaining as aide on the staff, returned to the on April 16, 1900. Commissioned

In December 1899, he transferred to the and remaining as aide on the staff, returned to the on April 16, 1900. Commissioned

After being detached from in February 1917, he was ordered to

After being detached from in February 1917, he was ordered to

In December 1918, he reported to the Office of Naval Intelligence, Navy Department, and on January 26, 1919, assumed command of the that was engaged in returning troops from

In December 1918, he reported to the Office of Naval Intelligence, Navy Department, and on January 26, 1919, assumed command of the that was engaged in returning troops from  On July 1, 1929, Rear Admiral Crosley reported as commandant of the Ninth Naval District, and commanding officer of the Naval Training Station, Great Lakes, Illinois. While in that assignment he served as a member of the Committee on Arrangements for the Century of Progress Expositions. Detached on August 2, 1932, he assumed command of Battleship Division 3, Battle Force, with his flag in the and later in the and . When detached on June 9, 1933, he was ordered to duty as commandant of the Fifteenth Naval District and commanding officer of the Naval Station,

On July 1, 1929, Rear Admiral Crosley reported as commandant of the Ninth Naval District, and commanding officer of the Naval Training Station, Great Lakes, Illinois. While in that assignment he served as a member of the Committee on Arrangements for the Century of Progress Expositions. Detached on August 2, 1932, he assumed command of Battleship Division 3, Battle Force, with his flag in the and later in the and . When detached on June 9, 1933, he was ordered to duty as commandant of the Fifteenth Naval District and commanding officer of the Naval Station,

officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," f ...

in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. He was a recipient of the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

, the second highest military decoration

Military awards and decorations are distinctions given as a mark of honor for military heroism, meritorious or outstanding service or achievement. DoD Manual 1348.33, 2010, Vol. 3 A decoration is often a medal consisting of a ribbon and a meda ...

for valor

Valor, valour, or valorous may mean:

* Courage, a similar meaning

* Virtue ethics, roughly "courage in defense of a noble cause"

Entertainment

* Valor (band), a Christian gospel music group

* Valor Kand, a member of the band Christian Death

* ' ...

. He subsequently advanced to the rank of rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

, to date from February 17, 1927, and was transferred to the Retired List in that rank on November 1, 1935.

Biography

Walter Selwyn Crosley was born in EastJaffrey, New Hampshire

Jaffrey is a town in Cheshire County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 5,320 at the 2020 census.

The main village in town, where 3,058 people resided at the 2020 census, is defined as the Jaffrey census-designated place (CDP) a ...

, on October 30, 1871, the son of a Universalist Church pastor. He was appointed to the U. S. Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy is ...

from the Fourth Congressional District

Congressional districts, also known as electoral districts and legislative districts, electorates, or wards in other nations, are divisions of a larger administrative region that represent the population of a region in the larger congressional bod ...

of Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the ...

and entered on September 9, 1889. He graduated on June 2, 1893, and served the two years at sea then required by law as a Passed Midshipman, first assigned to the Naval Academy training ship and next to the new cruiser, that was at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

, during the naval revolt against the Brazilian Government. In March 1894 he was attached to the that sailed by way of the Straits of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pas ...

to Mare Island Navy Yard

The Mare Island Naval Shipyard (MINSY) was the first United States Navy base established on the Pacific Ocean. It is located northeast of San Francisco in Vallejo, California. The Napa River goes through the Mare Island Strait and separates t ...

on her way to the Asiatic Station

The Asiatic Squadron was a squadron of United States Navy warships stationed in East Asia during the latter half of the 19th century. It was created in 1868 when the East India Squadron was disbanded. Vessels of the squadron were primarily inv ...

. The ship arrived at San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

in July 1894 during a railroad strike and while at Mare Island, Passed Midshipman Crosley was given command of a detail that manned a Gatling gun

The Gatling gun is a rapid-firing multiple-barrel firearm invented in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling. It is an early machine gun and a forerunner of the modern electric motor-driven rotary cannon.

The Gatling gun's operation centered on a c ...

loaded on a flat car

A flatcar (US) (also flat car, or flatbed) is a piece of rolling stock that consists of an open, flat deck mounted on a pair of trucks (US) or bogies (UK), one at each end containing four or six wheels. Occasionally, flat cars designed to carry ...

ahead of a locomotive

A locomotive or engine is a rail transport vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. If a locomotive is capable of carrying a payload, it is usually rather referred to as a multiple unit, motor coach, railcar or power car; the ...

with the purpose of dissuading the strikers so that trains might proceed without altercation.

Sino-Japanese War

Crossing thePacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

, arrived at Yokohama, Japan

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

during the Sino-Japanese War and proceeded to Chemulpo

Incheon (; ; or Inch'ŏn; literally "kind river"), formerly Jemulpo or Chemulp'o (제물포) until the period after 1910, officially the Incheon Metropolitan City (인천광역시, 仁川廣域市), is a city located in northwestern South Kor ...

, Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

whence Passed Midshipman Crosley was sent to Seoul

Seoul (; ; ), officially known as the Seoul Special City, is the Capital city, capital and largest metropolis of South Korea.Before 1972, Seoul was the ''de jure'' capital of the North Korea, Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea ...

with a United States Marine

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through com ...

guard as security for the American Legation. Promoted to ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

on July 1, 1895, he remained at sea and during the next three years served on the , , and . On March 31, 1898, he joined the as watch and division officer. On April 2, that year he assumed his first sea-command, the , and a month later was transferred to command of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

era armed- tug

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, suc ...

Spanish American War

Cuban Campaign

During the

During the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

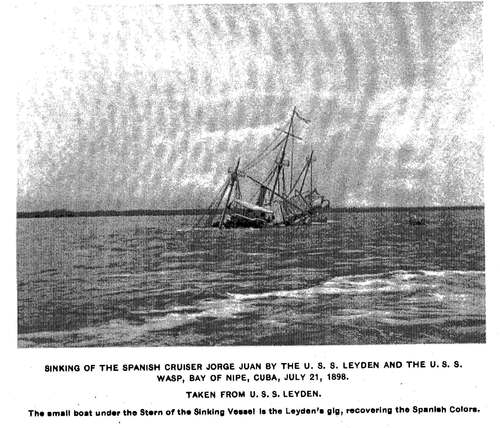

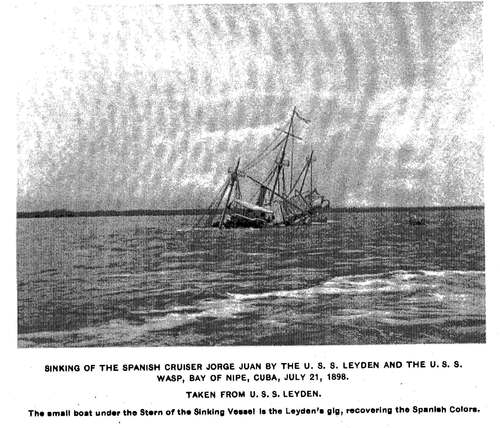

he was advanced two numbers in rank for eminent and conspicuous conduct on July 21, 1898, during the Battle of Nipe Bay. Commanding , part of a squadron that included the , and . Crosley took the lead in crossing a minefield in the dangerous, narrow channel. On entering under musketry fire from shore, together with ''Wasp'', they discovered the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-ste ...

'' Jorge Juan'' and engaged in a heated action until the remaining ships of the squadron arrived, at which time the enemy vessel was abandoned and sunk.

Puerto Rican Campaign

Two weeks later, at theBattle of Fajardo

The Battle of Fajardo was an engagement between the armed forces of the United States and Spain that occurred on the night of August 8–9, 1898 near the end of the Puerto Rican Campaign during the Spanish–American War.

Background

Proceeding ...

during the Puerto Rican Campaign, broadsides from Ensign Crosley's supported a landing party of thirty-five bluejackets from the coastal monitor that occupied the Cape San Juan lighthouse and defended sixty women and children of the prominent families of Fajardo

Fajardo (, ) is a town and municipality -Fajardo Combined Statistical Area.

Fajardo is the hub of much of the recreational boating in Puerto Rico and a popular launching port to Culebra, Vieques, and the U.S. and British Virgin Islands. It is ...

that had sought the Americans' protection from a superior Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

force of about one-hundred to one-hundred and fifty troops and cavalry the night of August 8–9, 1898. The Spaniards abandoned the attack after a couple of hours and with no American casualties. The next morning the women and children were embarked on which transported them to Ponce, Puerto Rico

Ponce (, , , ) is both a city and a municipality on the southern coast of Puerto Rico. The city is the seat of the municipal government.

Ponce, Puerto Rico's most populated city outside the San Juan metropolitan area, was founded on 12 August 1 ...

.

Philippine Insurrection

On September 12, 1898, Crosley reported to the training ship and was on duty at the Naval Academy from September 22, 1898, until April 1899, when he was ordered to the as watch and division officer, with the rank ofLieutenant (junior grade)

Lieutenant junior grade is a junior commissioned officer rank used in a number of navies.

United States

Lieutenant (junior grade), commonly abbreviated as LTJG or, historically, Lt. (j.g.) (as well as variants of both abbreviations), ...

. He reached the Asiatic Station

The Asiatic Squadron was a squadron of United States Navy warships stationed in East Asia during the latter half of the 19th century. It was created in 1868 when the East India Squadron was disbanded. Vessels of the squadron were primarily inv ...

, reporting to the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

as Aide on the Staff of the Commander in Chief, U.S. Asiatic Fleet, Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

John C. Watson on June 30, 1899. He volunteered for duty against the Insurrectos, and on October 8, 1899, in an engagement at Noveleta, Cavite

Cavite, officially the Province of Cavite ( tl, Lalawigan ng Kabite; Chavacano: ''Provincia de Cavite''), is a province in the Philippines located in the Calabarzon region in Luzon. Located on the southern shores of Manila Bay and southw ...

, Philippine Islands

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, he was wounded when "a spent ball" struck his leg.

Inter-war years

In December 1899, he transferred to the and remaining as aide on the staff, returned to the on April 16, 1900. Commissioned

In December 1899, he transferred to the and remaining as aide on the staff, returned to the on April 16, 1900. Commissioned lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

from March 3, 1901, he returned to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

via the , and served as watch and division officer on board until April 1902, when he reported for duty with the General Board, Navy Department, Washington, D.C. In January 1904, Lieutenant Crosley joined the , and in April that year, assumed command of the . On March 9, 1905, he was ordered to the for duty as flag lieutenant on the staff of Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

Robley D. Evans, the first commander in chief, US Atlantic Fleet

The United States Fleet Forces Command (USFF) is a service component command of the United States Navy that provides naval forces to a wide variety of U.S. forces. The naval resources may be allocated to Combatant Commanders such as United Stat ...

, and second in rank to Admiral of the Navy

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

George Dewey

George Dewey (December 26, 1837January 16, 1917) was Admiral of the Navy, the only person in United States history to have attained that rank. He is best known for his victory at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish–American War, with ...

.

Promoted to lieutenant commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding ran ...

in 1906, in December that year he was detached from staff duty and began a tour of shore duty as assistant to the equipment officer at the New York Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York (state), New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a ...

and later served in the Ordnance Department of that Yard. He had temporary duty on board the , taking passage on February 26, 1909, and from March 7 until June 27, he served as executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization. In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer, o ...

and navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's prima ...

of the . He had similar duty on board the until November, when he reported as navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's prima ...

of the . In July 1910 he had special temporary duty in the Bureau of Navigation, Navy Department, Washington, D.C., and on August 4, 1910, took command of the in English waters. In 1912 he was advanced to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain. ...

and served as aide to Vice Admiral Hugh Pigot Williams

Admiral Hugh Pigot Williams (1 September 1858 – 28 June 1934) was a British officer of the Royal Navy. In 1910–1912, while a Rear Admiral in the Royal Navy, he served as head of the British naval mission to the Ottoman Empire and Fleet Comma ...

of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

. Detached from the in April 1912, he returned to Washington, where he again served on the General Board of the Navy Department.

Haitian and Dominican Campaigns

In July 1914 he was detached to the asexecutive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization. In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer, o ...

. Promoted to captain, from June 30, 1915, he commanded the . ''Prairie'' was ordered to Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

and Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic during the American occupations, where Captain Crosley received fleeing foreign residents aboard his ship and landed forces that occupied the West Indies islands.

World War I

After being detached from in February 1917, he was ordered to

After being detached from in February 1917, he was ordered to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

as assistant naval attache; however, relations were severed with Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

before his arrival. His orders were changed to report to Petrograd, Russia as Naval Attache. He and his wife reached that city by way of Japan, Korea, China, and Siberia on May 7, 1917, a month after the United States entered World War I. The following year in Russia was one of constant danger for Captain and Mrs. Crosley. The Tsar's Government was disintegrating and in July 1917, when Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

captured Petrograd, the Crosleys were safely escorted under cover of night to the American Embassy by a Russian officer who risked his life to assist them. With the danger unacceptable for the mission, in April 1918, Crosley was ordered to leave Russia by way of Finland and Sweden. The Crosleys made their escape with the assistance of the American ambassador. During one night's train ride to Helsingfors, Finland, their passports were demanded nineteen times. In Finland, Captain Crosley took charge of a party of sixteen Americans and a Roumanian diplomat who had been trying to leave Russia for weeks. As they neared the frontier, Crosley arranged a truce between the Reds and Whites, whereby the party crossed the ice escorted by a Red general carrying a large American flag. Finally reaching Stockholm, Sweden

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropolita ...

, Captain Crosley received orders there to proceed to Madrid, Spain

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, as naval attache, where he reported on May 10, 1918, and remained until the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

.

Navy Cross

In 1920, Captain Crosley was awarded theNavy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

for his Russian diplomatic service in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. His citation reads, "For distinguished service in the line of his profession as Naval Attache at Petrograd, and for conducting a party of Americans out of Russia in April 1918, under difficult and trying conditions."

Postwar service

In December 1918, he reported to the Office of Naval Intelligence, Navy Department, and on January 26, 1919, assumed command of the that was engaged in returning troops from

In December 1918, he reported to the Office of Naval Intelligence, Navy Department, and on January 26, 1919, assumed command of the that was engaged in returning troops from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. He was transferred in May 1920 to command the doing similar transport duty for returning troops. On March 21, 1921, Crosley became assistant to the commandant of the Sixth Naval District, Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

. A month later he was designated commandant of the Seventh Naval District

The naval district was a U.S. Navy military and administrative command ashore. Apart from Naval District Washington, the Districts were disestablished and renamed Navy Regions about 1999, and are now under Commander, Naval Installations Command ...

, Key West, Florida

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Sigsbee Park, Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Isla ...

, with additional duty as commandant of the Naval Station and Naval Operating Base, Key West, and remained there until May 1923.

After duty afloat in command of the from June 11, 1923, until June 1925, he served as hydrographer, Bureau of Navigation, Navy Department, from June 29, 1925, until July 1927. As such he represented the United States in

Monaco

Monaco (; ), officially the Principality of Monaco (french: Principauté de Monaco; Ligurian: ; oc, Principat de Mónegue), is a sovereign city-state and microstate on the French Riviera a few kilometres west of the Italian region of Lig ...

at the International Hydrographic Conference, arriving October 22, 1926, There he was elected by the delegates of twenty-three countries represented to preside over the conference. During his tour of duty as hydrographer, he also served as a member of the United States Geographic Board. After his promotion to rear admiral in January 1927 (to rank from February 17, 1927) he was ordered to command Train Squadron ONE, Scouting Fleet Base Force, and remained in that command from August 1, 1927, until June 29, 1929. He again represented the United States as a delegate to the International Hydrographic Conference meeting in the Principality of Monaco on April 1, 1929, and upon his return had further temporary duty at the Hydrographic Office, Navy Department, before resuming command of Train Squadron ONE, his flag in the .

On July 1, 1929, Rear Admiral Crosley reported as commandant of the Ninth Naval District, and commanding officer of the Naval Training Station, Great Lakes, Illinois. While in that assignment he served as a member of the Committee on Arrangements for the Century of Progress Expositions. Detached on August 2, 1932, he assumed command of Battleship Division 3, Battle Force, with his flag in the and later in the and . When detached on June 9, 1933, he was ordered to duty as commandant of the Fifteenth Naval District and commanding officer of the Naval Station,

On July 1, 1929, Rear Admiral Crosley reported as commandant of the Ninth Naval District, and commanding officer of the Naval Training Station, Great Lakes, Illinois. While in that assignment he served as a member of the Committee on Arrangements for the Century of Progress Expositions. Detached on August 2, 1932, he assumed command of Battleship Division 3, Battle Force, with his flag in the and later in the and . When detached on June 9, 1933, he was ordered to duty as commandant of the Fifteenth Naval District and commanding officer of the Naval Station, Balboa, Canal Zone

Balboa is a district of Panama City, located at the Pacific entrance to the Panama Canal.

History

The town of Balboa, founded by the United States during the construction of the Panama Canal, was named after Vasco Núñez de Balboa, the Spa ...

. He served two years in that assignment, then had duty in July and August 1935 as a member of the General Board, Navy Department.

Rear Admiral Crosley was transferred to the Retired List of the U.S. Navy on November 1, 1935, and was relieved of all active duty, having reached the statutory retirement age of sixty-four years. He received a commendatory letter from the Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

, the Honorable Claude Swanson

Claude Augustus Swanson (March 31, 1862July 7, 1939) was an American lawyer and Democratic politician from Virginia. He served as U.S. Representative (1893-1906), Governor of Virginia (1906-1910), and U.S. Senator from Virginia (1910-1933), befor ...

, as follows: "The Department regrets your retirement from active service and takes this occasion to extend to you its heartiest congratulations and appreciation for your long and distinguished service to our Nation. During the time which you have so faithfully and efficiently served, you have witnessed many advancements in the morale, strength and efficiency of the navy; and you have the satisfaction of knowing that you have contributed to the accomplishment of these results. . . ."

Retirement

After his retirement, Admiral Crosley was elected president director of the International Hydrographic Bureau atMonte Carlo, Monaco

Monte Carlo (; ; french: Monte-Carlo , or colloquially ''Monte-Carl'' ; lij, Munte Carlu ; ) is officially an administrative area of the Monaco, Principality of Monaco, specifically the Ward (country subdivision), ward of Monte Carlo/Spélugue ...

, in April 1937, and served in that capacity until his resignation in June 1938 on account of ill health. He died on January 6, 1939, at Johns Hopkins University Hospital

The Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) is the teaching hospital and biomedical research facility of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, located in Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. It was founded in 1889 using money from a bequest of over $7 million (1873 mo ...

, Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore wa ...

, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

.

Admiral Crosley was a member of the Sons of the American Revolution

The National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR or NSSAR) is an American congressionally chartered organization, founded in 1889 and headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky. A non-profit corporation, it has described its purpose ...

.

Family

In 1895, Ensign Crosley married Pauline de Lannay Stewart (1871–1955) of Columbus, Georgia. They had two sons, Floyd Stewart Crosley (1897–1979) and Paul Cunningham Crosley (1902–1997). Both Crosley's sons graduated from theNaval Academy

A naval academy provides education for prospective naval officers.

See also

* Military academy

A military academy or service academy is an educational institution which prepares candidates for service in the officer corps. It normally pr ...

Classes of 1919 and 1925, respectively, and both retired as navy captains. In 1921, Lieutenant Floyd Crosley was seriously injured while serving as engineering officer on the when a boiler gauge exploded during a full-power trial run. Called to the fire-room by a report that a boiler had lost water, he reached there in time to receive the full force of the exploding glass that caused the loss of his right eye. He retired in 1926 but returned to active duty in October 1942 during World War II and served as a commander for the duration. His younger brother, Paul Crosley, served more than thirty years active duty in the navy, through World War II and the Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{ ...

.

Awards and decorations

In addition to the Navy Cross, Rear Admiral Crosley received the following medals:Sampson Medal

The Sampson Medal was a U.S. Navy campaign medal. The medal was authorized by an Act of Congress in 1901. The medal was awarded to those personnel who served on ships in the fleet of Rear Admiral William T. Sampson during combat operations in th ...

with ship's bar; Spanish Campaign Medal; Philippine Campaign Medal

The Philippine Campaign Medal is a Awards and decorations of the United States military, medal of the United States Armed Forces which was created to denote service of U.S. military men in the Philippine–American War between the years of 1899 an ...

; Haitian Campaign Medal (1915); Dominican Campaign Medal; and World War I Victory Medal with Overseas Clasp. He also received the following foreign decorations: Medal of Honor and Merit and Diploma awarded by the President of the Republic of Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and so ...

; Second Order of Wen-Hu, awarded by the Chinese Ministry of the Navy; and Commander of the Order of the Iron Crown

The Order of the Iron Crown ( it, link=no, Ordine della Corona Ferrea) was an order of merit that was established on 5 June 1805 in the Kingdom of Italy by Napoleon Bonaparte under his title of Napoleon I, King of Italy.

The order took its name ...

, conferred by the Italian Government.

Namesake ship

Mrs. Walter S. Crosley was Sponsor for thedestroyer escort

Destroyer escort (DE) was the United States Navy mid-20th-century classification for a warship designed with the endurance necessary to escort mid-ocean convoys of merchant marine ships.

Development of the destroyer escort was promoted by th ...

USS ''Crosley'' (DE-226) named in honor of her husband and launched on January 1, 1944. Prior to its commissioning on October 22, 1944, the ship was converted to a high speed transport and re-designated .

References

: {{DEFAULTSORT:Crosley, Walter 1871 births 1935 deaths People from Jaffrey, New Hampshire United States Navy rear admirals United States Naval Academy alumni Naval War College alumni American military personnel of the Spanish–American War United States Navy personnel of World War I Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) Burials at Arlington National Cemetery